Gram Parsons

- Tara Crutchfield

- Jun 30, 2022

- 53 min read

Polk’s “Uncommonly Musical” Sixties, Gram Parsons, and a Cosmic Collaboration to Save the Derry Down

The sixties in Polk County, Florida, claimed a transcendental sum total of talent. Some kind of musical magic was in the water, or maybe the stars. It was the birthplace of the Father of Cosmic American Music, Gram Parsons, along with a broad list of other epochal musicians and entertainers who emerged from these sleepy southern towns. Garage band kids from Winter Haven, Auburndale, and Eloise would go on to become acclaimed songwriters, comedians, and performers. Something celestial must have laid at the junction of time and place – in this slice of Florida throughout the sixties – a place Bob Kealing called “uncommonly musical.”

The effects of Elvis Presley and the Beatles can’t be discounted, said Kealing, the author of Calling Me Home: Gram Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock. They were ubiquitous on the radio, the paramount of celebrity, and spent significant time in the Sunshine State, Presley in 1956 and the Beatles in 1964. Elvis even performed a show at the Polk Theatre in Lakeland on August 6, 1956.

“That was huge for people because it was the dawning of youth culture – it was the dawning of music that was made for teens,” Kealing said. “Rock and roll spoke to a lot of teen yearning and feelings of angst and anxiety.”

Musician, comedy writer, and childhood friend to Gram Parsons, Jim Carlton suspects the showbiz spirit of Florida’s first theme park had something to do with it. Before moving from Chicago, Carlton’s parents took him to see a film shot at Cypress Gardens, Easy to Love (1953), starring Esther Williams and Van Johnson, to give their son a glimpse of his new home. “Cypress Gardens was this little hub of show business, a little oasis in the middle of Florida,” he said.

The collaborative culture of band hopping, jam sessions, and playing gigs in youth centers across Central Florida certainly played a role. “My dad always said the best thing you can do is play music with other people,” Carlton said. And he was right. Local garage bands like the Legends, the Dynamics, and the Steppin’ Stones produced prolific musicians, like Jim Stafford, Jon Corneal, and Les Dudek.

Lakeland-born, Auburndale-raised Bobby Braddock was a product of Polk County’s musical pinnacle. A pianist for the Dynamics, Braddock has had a series of No. 1 hit songs spanning five decades. He and Curly Putman co-wrote “D-I-V-O-R-C-E,” recorded by Tammy Wynette, and George Jones’s chart-topping classic “He Stopped Loving Her Today.” Braddock paid homage to his hometown in his autobiography Down in Orburndale: A Songwriter’s Youth in Old Florida.

The late Carl Chambers, who passed away in 2020, was another Auburndale musician and songwriter to make a hit, composing Alabama’s “Close Enough to Perfect.”

Kent LaVoie, who performs as Lobo, grew up in Winter Haven. The singer-songwriter has had major chart success with songs like “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo” and “I’d Love You to Want Me.”

And, of course, there’s Gram Parsons – a country rock cult figure and genre pioneer. He may not have cut his teeth on twang, but Gram certainly became a country music tastemaker and luminary. Parsons’s backstory is imbued with equal measure talent and tragedy. The winsome Winter Haven-born musician carried an earnestness in his voice that endears listeners almost fifty years after his death. Whether he’s bluesy belting “Cry One More Time for You” or giving a subtle Elvis lip snarl and afflicted gaze while singing “Hot Burrito #1,” those who discover Gram don’t soon forget him.

Parsons’s renown is most often attributed to his later work with the International Submarine Band, the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Gram and the Fallen Angels, his solo work, and collaborations with Emmylou Harris. One jewel on the crown of his legacy was co-writing “Hickory Wind” with Bob Buchanan, released on the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo album in 1968. The first few guitar twangs of the song are a promise only Parsons can make good on, as he delivers the first line, “In South Carolina…” with his lofty southern sweetness.

Two famous friends and collaborators cardinal to his career and personal life were Rolling Stones guitarist and frontman Keith Richards and a young Emmylou Harris, whom author Bob Kealing referred to as Parsons’s “vocal soul mate.” During Harris’s induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame decades after Parsons’s death, his enduring memory and mark are present. While introducing Emmylou, Country Music Hall of Fame CEO Kyle Young called Gram the one “who would help [Harris] understand the true power, poetry, purity, and perhaps the political righteousness of country music as the voice of, by, and for the people.” The enigmatic chemistry between Emmylou and Gram is the stuff of legend, living on in perpetuity. Swedish folk duo, First Aid Kit, called their songs “quite the musical revelation.” Inspired by Gram and Emmylou’s relationship and “the joy and magic of singing with someone you love,” the pair released the song “Emmylou” in 2012. Harris gently wiped tears from her cheek during the 2015 Polar Music Prize ceremony as the pair sang “Emmylou.” During the chorus, the sisters lilt:

I’ll be your Emmylou and I’ll be your June

If you’ll be my Gram and my Johnny too

No, I’m not asking much of you

Just sing little darling, sing with me

In a 2010 Rolling Stone article listing Gram Parsons as #87 in the list of the “100 Greatest Artists” of all time, friend Keith Richards called Gram “everything you wanted in a singer and a songwriter,” and said, “we can’t know what his full impact could have been. If Buddy Holly hadn’t gotten on that plane, or Eddie Cochran hadn’t turned the wrong corner, think of what stuff we could have looked forward to, and be hearing now. It would be phenomenal.”

Parsons’s former bandmate and “Spiders and Snakes” songwriter, Jim Stafford, shared the sentiment. “He was headed in the right direction if he had lived long enough. The sad part is none of us will ever get to know what he could have accomplished because he really was a gifted young man. He really was.”

But, before he would carve out a cosmic career, cement his name in country rock history, and leave the world too soon, Gram Parsons was just another kid from Winter Haven, Florida who loved Elvis.

THE GRAM SCHEME OF THINGS

Gram Parsons was born Ingram Cecil Connor III in Winter Haven, Florida. The Conners moved to Waycross, Georgia where his father, Cecil “Coon Dog” Conner II, worked in a family box plant. In Waycross, Gram saw an up-and-coming Elvis Presley at the city auditorium in February 1956. Gram Parsons biographer Bob Kealing noted that the effect this had on Gram was “immediate and long-lasting.” The pursuit of music and celebrity would be a fixture in Parsons life from this moment forward.

Gram’s maternal grandparents were the exceedingly wealthy Winter Haven citrus family, the Snivelys. Patriarch John Snively was a fertilizer salesman turned real estate investor and citrus millionaire. The Snively mansion can still be seen in LEGOLAND Florida Resort today as John was the one who’d sold the land on which Cypress Gardens was built. This charmed citrus-money lineage guaranteed Gram a rather healthy trust fund.

That trust fund didn’t mean he would be spared tribulation though. Parsons lost his father to suicide on December 23, 1958, and his mother to alcoholism on the day of his high school graduation from the Bolles School. Gram’s own death at 26, in Joshua Tree, California, on September 19, 1973 and the circumstances that followed have unfortunately – at least partially – cast a shadow over his musical contributions.

Kealing felt compelled to tell Gram’s story for this reason. “It really felt like Gram had an unfinished life,” he said. The overemphasis on the morbid circumstances surrounding Parsons’s death in the California desert inspired Kealing to write a book that forwent the macabre for what mattered. During a 2013 book signing at the Winter Haven Public Library, the author said, “I was looking for some sort of redemption in Gram Parsons’s story. Less about the hype and sensationalism, more about the rich fabric of the definative places that he called home. The people with whom he played and those who carry on his legacy. That’s why I wanted my book to be a song of the south — Gram’s story rooted in places like Winter Haven and Waycross — not LA, not Joshua Tree, California.”

In the same spirit, this article will focus on stories from Parsons’s formative years and career – on his contemporaries and friends – those who shaped the music scene within and beyond the orange groves, pine scrub, and murky lakes of Polk County, Florida.

Following the death of his father in 1958, Gram moved with his mother, “Big Avis” Connor and younger sister, “Little Avis” back to Winter Haven. It was here that Gram would step into the limelight, and never really leave.

The first band Parsons played with was called the Pacers. In 1960, he sang to a crowd of some 50 kids at the Dundee train depot. Gram would eventually move on to start his own band called the Legends. There are several iterations of the band throughout the years seeing members come and go. The Legends started in 1961 with Gram playing guitar and piano, Jim Stafford from Eloise on lead guitar, Lamar Braxton on drums, and his friend Jim Carlton on upright bass.

Jim Carlton met Gram Connor in 1959 when he transferred to St. Joseph Catholic School. “I am not Catholic, and neither was he, but my folks were told I’d get a better education there and I probably did. It was a heck of a lot more fun than public school,” Carlton said.

Jim’s father, Chicago musician Ben Carlton, moved his family to Winter Haven in 1954 to work in-studio for the radio show Florida Calling. Contracted by the Florida Citrus Commission, the show was broadcast five days a week from the Florida Citrus Building.

Within ten minutes of meeting, Jim and Gram became friends, united by a sharp sense of humor. Carlton described Gram as a bright kid, and said, “Even then he was very magnetic.” In a time where boys called one another by their last names, Carlton took notice that for the young Connor boy – everyone just called him Gram.

At school, the nuns would task Gram with watching over younger classes if a teacher had to step out. He was known to tell stories to keep the children entertained. “He was confabulous,” Carlton laughed. “If you believed everything Gram ever said, you were a fool. He spread a lot of his own legend if you will. […] But he was so damn good at it.” In fact, Gram would go on to ‘spread his own legend’ while at Harvard. In a comical turn of events, he convinced the school paper that he and his college band, the Like, had signed with RCA Records, a falsehood picked up by The Boston Globe with even more fabulous claims tacked on – carried further down the line, the following week by The Tampa Tribune.

Storytelling aside, there was a maturity about Gram, gilded with boyish charm. Carlton described Parsons as a nonjudgmental character who rejected the prejudices that were a hallmark of the 1960s deep south. Adults like Carlton’s father remarked on Gram’s intellect.

A stylish dresser and ever ‘his own man’ as Carlton described him, Parsons made other boys envious when girls would ogle over him. “He would take that in stride,” his friend said. Gram had even been hit a few times by jealous boyfriends – but he could take a punch. Parsons’s good looks and style would be a point of recognition for the rest of his life. His rhinestone-studded Nudie suit embroidered with naked ladies, pot leaves, pills, and poppies with a bold red cross radiating rainbow rays on the back remains an epic piece music fashion history. During a talk at a Brunswick, Georgia library in 1992 journalist Stanley Booth, who traveled with the Rolling Stones and wrote the book The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, described the first time he saw Gram entering a room with Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. Booth, who also grew up in Waycross, Georgia, remembered Gram as “very handsome” and said he “looked like the sweetheart of the rodeo” with his long brown, frosted blond locks. “The Rolling Stones were famous – they were really famous. They were cool. […] And here’s this guy with them, who’s better looking, he’s got better clothes, he had better everything,” Booth said.

While young Gram did impress parents and girls, the sharpdressed kid never shied away from a good time. He and pal Jim Carlton much preferred the company of the adults in their lives. “They had the booze, and they had the cigarettes, and they had the parties. It kind of eclipsed our high school friends,” Carlton said. The dynamic duo would put together routines to entertain during get-togethers. Gram would play the banjo or guitar, with Carlton noodling on bass or guitar. “We worked up a Smothers Brothers routine once,” Carlton said. “Gram would have made a tremendous comedy writer. He had a terrific sense of humor – very sarcastic.”

Carlton would go on to have a noteworthy comedy career of his own. He kept in touch with Legends bandmate, funnyman, and guitar hero, Jim Stafford. Carlton has written with the likes of Stafford, the Smothers Brothers, Gallagher, and Joan Rivers. He traveled all around casino towns and LA as a writer, thanks to Jim Stafford who Carlton called a “tremendous influence” on his career.

Gram’s quiet maturity didn’t get in the way of goofing around with his friends either. Like when the Legends would go out of town for a gig and stay at a hotel, they’d stack beer cans in a pyramid against the mirror. Carlton said, “There was an adolescent sense of fun with him around. He loved having people around, loved having pals come over. He’d always have somebody hanging out because I think there was a sadness, and a melancholy to him.”

Stepfather Bob Parsons, whose last name Gram took after Parsons adopted him, was ceaselessly supportive of Gram’s musical aspirations. Bob bought Gram a Volkswagen bus with ‘The Legends’ inscribed along the side before he even had a license. Consequently, older bandmates like Jim Stafford would have to drive them to and from gigs.

The Legends line-up would shift in 1962 when Gram recruited the Dynamics band members, two boys from Auburndale, Gerald “Jesse” Chambers and Jon Corneal. Gram was on keyboards, guitar, and vocals, with Jim Stafford on lead guitar, Chambers on bass and vocals, and Corneal on drums. Sam Killebrew, now a Florida Representative, was their band manager. He still has the business cards to prove it.

Corneal appreciated Gram’s ability to land well-paying bookings, like a gig playing a horse show banquet in the ballroom of the Haven Hotel. The Legends played teen centers, holiday parties, hotel lounges, high school dances, and events at Nora Mayo Hall. “You have to have a place to be bad,” Carlton said. “Often the place to be bad is at teen centers and Holiday Inn lounges.”

The Legends made several appearances on WFLA channel 8’s musical television show, Hi-Time, along with other Polk County bands like the Dynamics. “Close Enough to Perfect” songwriter, and cousin to Jesse Chambers, Carl Chambers took a reel-toreel recording of the Legends playing “Rip It Up” and the Everly Brothers’ “Let It Be Me” during an appearance on the show. The Legends were a hit and won Hi-Time’s Band of the Year.

On the heels of his time leading the Legends, Gram entered his folk phase. Lakeland’s Dixieland district was a magnet for musically inclined and interested teens of the 1960s. The city even had its own happening coffeehouse called the Other Room, where folk artists performed. Casswin Music (where Gram got his first Fender Stratocaster guitar) was situated on the same stretch of Florida Avenue, along with Fat Jack’s Deli which opened in 1963.

“We’d all go over there together and goof off,” said Legends drummer Jon Corneal. He remembered Jay Erwin, part-owner of Casswin Music. Erwin wrote and funded Gram’s single, “Big Country.” Beyond his music store, Erwin’s mark on Lakeland’s music history was indelible. The Casswin Music owner was instrumental in organizing the Lakeland Civic Symphony in 1965, now the Lakeland Symphony Orchestra, even acting as their first conductor.

“He was a bee-bopper […], and he talked cool,” Corneal said of Erwin. “We’d go over there and get cool-talking lessons. It was ‘man this’ and ‘man that.’ He was the first person to ever call me ‘man.’ I was just a teenager – I liked being called ‘man.’” The boys would head over to Fat Jack’s Deli next door, where they’d go for a hot pastrami on rye, and Corneal would eat his weight in kosher pickles.

The Other Room, a coffeehouse and folkie spot, started by Lakeland guitarist Rick Norcross, was a regular haunt and performance venue for Gram, and a central part of his folk identity of the mid-sixties.

Jim Carlton still has the 45-rpm acetate thought to be Parsons’s earliest studio recording. Gram recorded two acoustic tunes in recording engineer Ernie Garrison’s Lakeland home: “Big Country” and “Racing Myself with the Wind.” “Those were his first efforts at songwriting,” noted Carlton. Well, that, and all his compositions to flatter the girl du jour, songs like “Pam” and “Joan,” which Jon Corneal had accompanied him to record in a modest studio inside Casswin Music.

Like his buddy Gram, Carlton played the folk scene as he joked, through “the folk music scare of the late 60s.” He went on to play on the same circuit and become friends with prolific singersongwriter and “Florida Troubadour,” Gamble Rogers. He later joined a show trio called Solomon, Carlton and Jones which performed shows around Disney. The group was a regional darling with regular photos and write-ups in the newspaper.

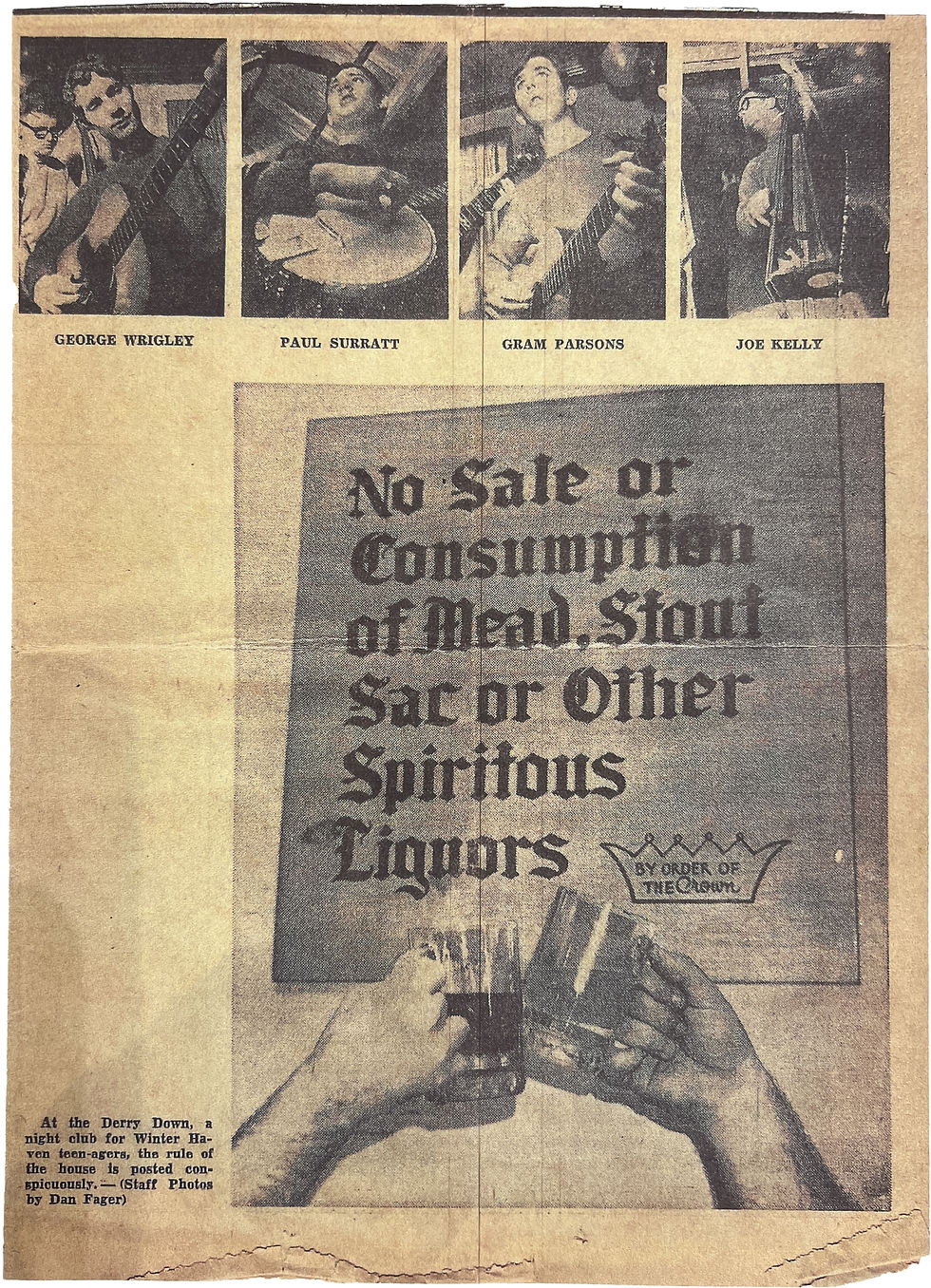

Gram joined his first professional band, a Greenville, South Carolina group called the Shilos, in 1963. Later the band would record “Big Country” together.

In April of 1964, the Shilos made a trip to Chicago on the dime of Cypress Gardens owner Dick Pope, tasked to make promotional recordings for the park in preparation for a visit from King Hussein of Jordan. Author Bob Kealing spoke with Shilos’ banjo player, Paul Surratt, about the trip in his book:

Surratt remembered the Shilos recording five or six songs in Chicago, including “Julie-Anne,” a New Christy Minstrels song Gram convinced his confederates he’d written. There was also a jaunty tune Gram actually did write as a kind of Cypress Gardens theme, “Surfinanny,” patterned closely after a song called “Raise a Ruckus Tonight.” It kills Surratt to this day that the other songs recorded were left at the studio and apparently lost to history.

The Shilo’s returned to Winter Haven later that year for another special occasion – the opening of the Derry Down. Bob Parsons wanted to gift his stepson a space he and his buddies could play whenever he was in town. Gram’s very own club was hosted in a nondescript warehouse on Fifth Street in Winter Haven. “He and Avis encouraged Gram’s musical pursuits,” Kealing said. “It was far from perfect in their own home and in a sense, Gram was raising himself. But I don’t think there’s any doubt that they opened the Derry Down as a teen club to encourage Gram’s musical talent.”

The club’s name and theme were Old English-inspired. The Derry Down menu included Derryburgers and Downdogs, prepared by Gram’s stepdad. “Bob Parsons was cheffing. He loved to do that more than just about anything,” Carlton said. The teen club served up nonalcoholic beverages befitting the Old English motif including a Wales Sunset, Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Hotspur.

In a Tampa Tribune article Gram commented, “We were really going to go old English, but the trouble is nobody here understands it. Even Hotspur is pretty far out for Winter Haven. All they want to know is what’s in it.”

The article notes that kids would pay “a dollar a head to hear Gram Parsons and the Shilos, a merry band of teen-age folk singers with surprising talent.” Derry Down patrons had to show identification at the front door to prove they were under 21 to get in.

The stage was set up along the right wall as guests walked in. There was a small kitchen for Bob Parsons to cook the burgers and hot dogs. In the ladies bathroom was a vanity table and chair for girls to powder their noses.

Jim Carlton described the opening of the Derry Down, on December 20, 1964, as an affair attracting Winter Haven’s well-to-do socialites – the elbow rubbers and friends of Gram’s moneyed mother “Big Avis.” Carlton said, “Opening night was a soiree for the ‘e-lite and the po-lite’ as we’d call it in Winter Haven.” Both Carlton’s mother and Big Avis donned fur stoles for the event.

Radio station WINT was on-site to simulcast the Shilos performance from the grand opening, and Carlton sat stageside with a reel-to-reel recorder for the concert. He still has the recordings.

Jon Corneal remembers the espresso machine Gram brought into the Derry Down – an almost alien luxury in 1960s Winter Haven, rumored to be the first of its kind here. “I’d never heard of an espresso machine,” Corneal said.

The Derry Down building on Fifth Street would later become the Pied Piper, and the Derry Down teen club moved to Cypress Gardens Boulevard.

By the summer of 1965, Gram had graduated high school, his mother had died, and the Beatles wave had crashed into the United States, ebbing the folk era out to sea. Parsons had left the Shilos and found himself at a career crossroads. That summer, between his time in Greenwich Village and Harvard, a dejected Gram shared his frustrations with Jim Stafford at his Winter Haven home. “Everybody that I knew was trying to figure out where our place was in all of this,” remembered Stafford. “He was a little bummed out.”

There, Stafford gave Gram the advice that would change his musical trajectory. “I said it without an ounce of thought,” Stafford said. He told Gram that with his long hair and good singing voice, “Well, you should be a country Beatle.”

Modest about his role in Gram’s subsequent genre migration, Stafford laughed and said, “He probably thought that was stupid. […] At the moment, I don’t think that sounded so hot to him.”

Gram must have mulled that over harder than Stafford realized at the time, because he would later tell Jim Carlton, that advice was a catalyst for his country rock career.

“Gram wanted to be a celebrity, that was first and foremost,” Carlton said. After learning to play “Steel Guitar Rag,” a twangy tune by country western crooner Bob Wills, he played it for Gram at his house. Gram said, ‘Carlton, what are you doing?’ and sat down at the piano to play some Floyd Cramer country licks, poking fun at his pal. “So, he didn’t give a damn about country music then,” Carlton said. “But he was grooming himself to be a celebrity of some kind. […] Somebody had said that if he’d have grown up in Minnesota, he would have figured out a way to make polka music hip.”

Where someone like Jim Stafford would spend hours a day mastering his guitar, Gram was more unabashedly interested in the star power of it all. Not to say the music wasn’t important to him, just if being a country Beatle was going to bring him fame and acclaim, a country Beatle he would be. “Gram, as I used to say, he’s about as countryfied as Gore Vidal,” Carlton said. “Nevertheless, he became a wonderful exponent of country music.”

The day after Christmas, 1965, Gram Parsons picked up an acoustic guitar for an impromptu recording session at Jim Carlton’s house. The latter had received a Sony 500 reel-to-reel recorder from a Pan Am pilot friend who brought it over from Tokyo. “It was the best toy train set a musically inclined boy ever had,” he said.

Gram wanted to share music he’d pick up from his time in Greenwich Village and a few songs he’d written. “He’d come home with these terrific songs by Fred Neil or [....] Bob Dylan,” Carlton said. “He had these terrific songs and wanted to share them with somebody who would appreciate it. They certainly weren’t going to make their way to Winter Haven.” These recordings would be some of the last vestiges of Gram Parsons’s folkie persona.

In 2000, Carlton co-produced the album Gram Parsons: Another Side of This Life, with Bob Irwin on Sundazed Records. “What’s significant is that these were during his folk music era,” he said. These “lost recordings of Gram Parsons” as the album cover reads, include music from those 1965 recordings, along with some from the year following, including tracks “Another Side of This Life,” “Codine,” and “Brass Buttons.” The album has sold over 20,000 copies worldwide and continues to garner interest from “completionist” Gram fans and the music industry the world over. “It is beautiful,” said Parsons fan and founding father of the Derry Down Project, Gene Owen. “It’s a transitional Gram.”

Gram could play a country tune like “Together Again” or “Love Hurts” and inspire goosebumps if not tears. Carlton said, “Give it to Gram and he brought something special to it that would touch people, and in a nutshell that was his magic. He was very soulful, and it was genuine.”

Perhaps this is what Jim Lauderdale experienced the first time he heard Gram. Cosmically gifted in his own right, two-time Grammy-winning singer-songwriter Jim Lauderdale looks at Gram Parsons‘s like the sun. The soul and sincerity permeating Parsons’ catalog is nothing short of spiritual for the musician who has written for George Strait, Patty Loveless, George Jones, the Dixie Chicks, Gary Allen, and Elvis Costello.

Of Parsons, Lauderdale said, “It was an important musical event when I first heard him – like hearing the Beatles for the first time or George Jones or Ralph Stanley – those musical moments where you remember exactly where you were and what you felt the first time you heard them.”

The first album Lauderdale picked up with Gram’s soulful country sound was Grievous Angel. He said, “From the very first song, all through the album, I was transfixed.” Eager to get his hands on anything Parsons was involved with, Lauderdale sought out his other music from GP to Sweetheart of the Rodeo and The Gilded Palace of Sin. He read interviews with Gram and those associated with him, and biographies of the late musician – the first of which would go on to inspire the song, “King of Broken Hearts.”

Lauderdale wrote “King of Broken Hearts” as a tribute to Gram Parsons and George Jones after reading Gram Parsons: A Musical Biography by Sid Griffin. Lauderdale said, “I read about a party that Gram was at. He was playing George Jones records, and he started crying, and he said, ‘That’s the king of broken hearts.’”

He released the song, produced by Rodney Crowell and John Leventhal on his 1991 Planet of Love album. The following year, George Strait included it, as well as another of Lauderdale’s songs, “Where the Sidewalk Ends” on his record, Pure Country.

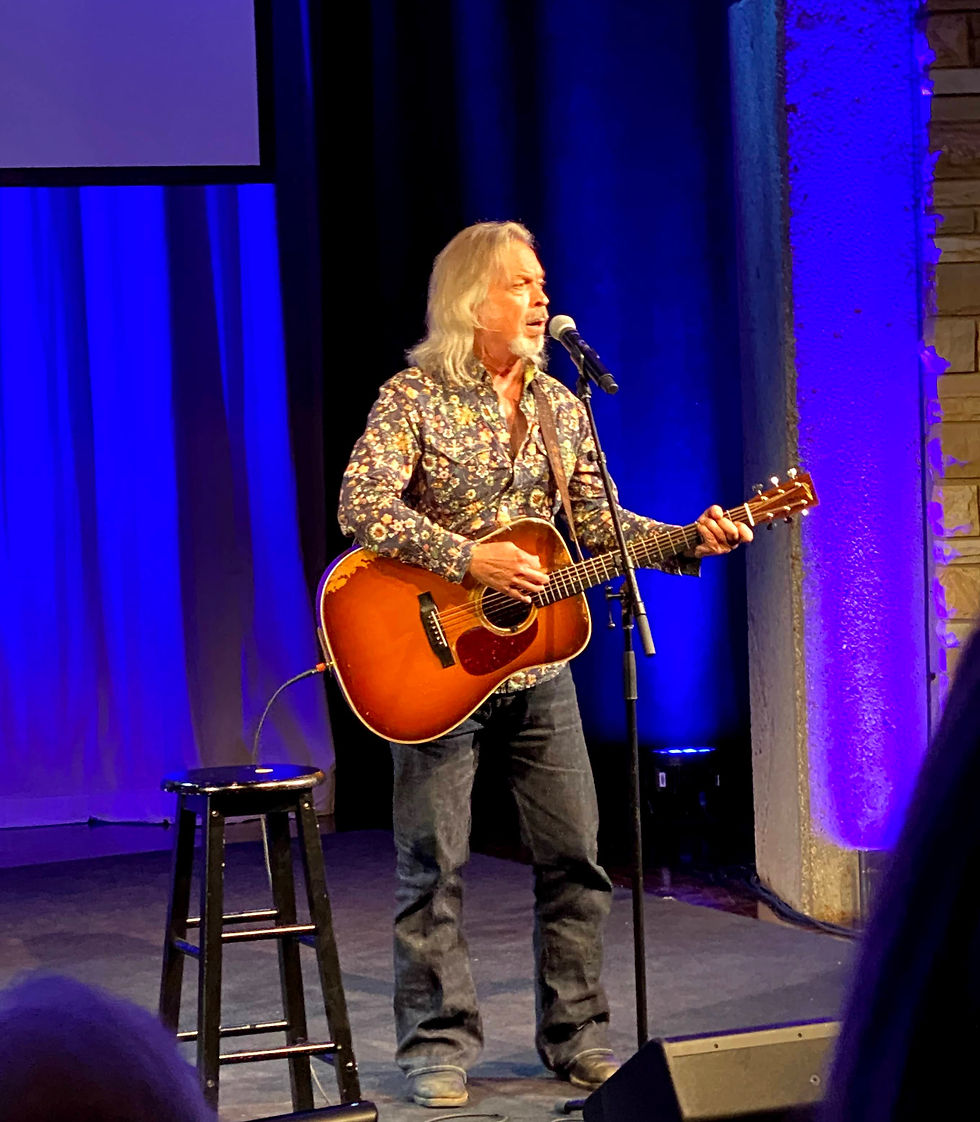

Jim Lauderdale sings “King of Broken Hearts” at just about every show. “I think about Gram when I’m singing it.” Lauderdale would get the chance to sing that song and think about Gram in a place that has become sacred to his legacy and his hometown – Gram Parsons Derry Down. But first it would need to be resurrected.

Gram Parsons remains a holy man for those who worship at the altar of good, honest music. But, he wasn’t the only one of his friends and contemporaries to make it out of Winter Haven, or to make music history, for that matter.

“SPIDERS AND SNAKES” & JIM STAFFORD

“If you don’t know it – practice, practice, practice. That’s what I did when I was a kid. All the other boys would be out practicing football, but I practiced the guitar, and I’m glad I did because it paid off… I can kick this guitar 60 yards,” Jim Stafford said to a roar of laughter from the audience during an appearance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. In another performance, jokes are peppered between flinger-blurring licks of “Malaguena” and “Flight of the Bumblebee” with giggles and applause in no short supply. A renaissance man, if ever there was one, Stafford is a maestro of hair-raising guitar picking and side-splitting comedy routines. A self-taught multi-instrumentalist, he plays fiddle, piano, banjo, organ, and harmonica. However, Stafford’s main instrument remains his trusty guitar. “I was really serious about the guitar,” Stafford said, “and I still am.”

His musical career began at his home in Eloise. He can still remember his neighbor and friend Wayne Simmons getting a beautiful red guitar from his brother, who’d brought it back from Germany. The two would play together – Stafford on his dad’s guitar. Wayne Simmons would go on to write the song “Gibson Girl” on the Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed album, Sneakin’ Around.

He may have joked around about practicing, but it was something he did religiously. Stafford kept a guitar on hand at Quality Cleaners, the family dry cleaning business, in Eloise, where he worked for his dad. He learned to read music from Jim Carlton’s father, Ben, at their family music store, Carlton Music Center. “I wanted to learn how to read music, and Ben Carlton was a studio musician, a quality musician who came to Florida with a band,” he said. Stafford’s intuition on the guitar and drive to practice earned the admiration of his peers. Even guitar teacher Ben Carlton was in awe of the young musician. Jim Carlton remembered that his dad didn’t particularly have the time or want to teach, but he made an exception for Stafford. “He saw that Jim Stafford was such a talented kid he couldn’t help himself,” Jim Carlton said. “In fact, he didn’t even charge money for the first several lessons.”

Stafford was in a few garage bands with other young Polk County musicians of the ‘60s, including several iterations of the Legends. Kids like Gram Parsons and Jim Carlton looked up to Stafford. “He was our avuncular older brother,” said Carlton.

In Calling Me Home author Bob Kealing refers to these Polk County musicians whom Gram “befriended and benefited from” as “a constellation of singers, songwriters, and entertainers on the rise.” The self-effacing Stafford was but one of the stars in that mellifluous constellation of charisma and knack. He reflected on his garage band days, “Sometimes we’d be playing with a couple of guys from Auburndale, a couple of guys from Winter Haven. There were some good people over there.” He tipped his hat to the talent of Bobby Braddock as well as Carl Chambers, calling his song “Close Enough to Perfect,” “one of the best country songs I’ve ever heard.”

In high school, Stafford and his buddies would often rehearse in his living room, and on Friday and Saturday nights, they’d load into someone’s car or Gram’s VW bus to play a Central Florida teen center. Back then, Stafford said, “I could play guitar alright, and a couple of the guys in the band would sing. It wasn’t the kind of band that we got together often and worked up complex arrangements or any of that kind of stuff. […] It was almost like kids pretending to be a band.”

Playing in bands was fun for Stafford, but he was more interested in being an entertainer than a rockstar. He often went to Christy’s Sundown Restaurant in Winter Haven to watch piano bar comics. “They’re fellas who sit at a piano, and they talk to the audience and sing songs and tell jokes,” he said. One of his favorites was Tampa-based comedian Pat Henry.

A young Jim Stafford would pick up the piano comics’ souvenir albums and listen to them again and again. “I learned quite a bit about how to talk to an audience, how to tell a joke, how to play a song they might like, how to get them to sing along – all of the things I could possibly learn about being an entertaining guitar comic. I guess that might have been what I was,” he said.

Stafford said he worked much harder afterward on becoming a single act. “I was always trying to write songs and jokes.” He thought if he could entertain, tell a few jokes, and play his guitar well, he might be able to make a living playing bars and restaurants and lounges. “That’s when I put my guitar in the back of my dad’s cleaning truck and drove out to the Dundee Holiday Inn and got a job playing with my guitar. I really never looked back after that,” he said.

Time spent performing at bars and hotel lounges sharpened Stafford’s comedic and musical abilities. “The perfect thing for me was to find places where I could work just about every night of the week so I could try my material.” Stafford would record his performances and listen back to his delivery to make adjustments.“My guitar playing was pretty good, and I worked on funny songs because I wasn’t much of a singer, so I thought I’d just do these little talking songs.”

In 1974, Stafford would release a song he wrote called “Swamp Witch” on his self-titled album, co-produced by another Winter Haven native, Kent ‘Lobo’ LaVoie. The single would spend one week on the U.S. top 40 charts, peaking at No. 39. Stafford followed this ‘moderate’ chart success with his version of David Bellamy’s, “Spiders and Snakes,” which he re-wrote in the bedroom of his childhood home in Inwood. The song was a hit.

“That’s a simple song, but I worked on it for quite a while because I knew there was something catchy about it,” he said. That song, which he would perform in 1976 alongside Dolly Parton on her nationally syndicated television show, went on to chart at No. 3 and sell 2.5 million copies. Stafford credits “Spiders and Snakes” for launching him onto stages across Reno and Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe, opening for musical icons from Bruce Springsteen and the Earl Scruggs Revue to Ike and Tina Turner.

“Looking back on it, it was thrilling because I started off in these little lounges, trying to write songs and do funny things and play the guitar as good as I could,” he said. “I kept at it and kept at it and got good enough to attract the attention of record people. Next thing I know, I had some records that did very well and moved out to LA.”

The “Spiders and Snakes” songsmith’s talents weren’t relegated to music and comedy. “Whenever there was some aspect of entertainment that I could get my hands on or figure out how to do myself, I would do it,” he said. Stafford had quite a few film roles over the years, including Any Which Way You Can (1980) starring Clint Eastwood (for which he wrote the song “Cow Patti’’), cult horror-comedy Blood Suckers from Outer Space (1984), Kid Colter (1984), Gordy (1994), and guest appearances in television series The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. Stafford made 26 appearances on The Tonight Show and hosted the ABC summer variety series The Jim Stafford Show as well as Those Amazing Animals with co-hosts Burgess Meredith and Priscilla Presley.

In 1990 Stafford opened The Jim Stafford Theatre in Branson, Missouri, where he brought in other first-rate musical acts and serenaded, wise-cracked, and played some of his greatest hits like “My Girl Bill” and “Wildwood Weed” to crowds for decades. He continues to do live performances, shining on audiences across the Sunshine State.

AN AUBURNDALE RAMBLIN’ MAN

Born on the naval base at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, Les Dudek moved to Auburndale, Florida, the year he turned seven. For Dudek, the move was marked by Buddy Holly’s plane crash. “That’s all I heard on my little nine-volt transistor radio,” he said. Orange blossoms, pine trees, and guitar chords made up the ethos of Dudek’s upbringing in the south. He remembers trips to Carlton Music and getting out of school to smudge pot orange groves when temperatures threatened to drop.

His sister was about four years older than Les. “She was always up on the latest and greatest” when it came to music, he said. He’d hear what she was listening to through their bedroom walls. As a result, Dudek was raised on a steady diet of Elvis Presley and the Beach Boys. As her musical tastes shifted towards the “Stupid Cupid” and “Lipstick on Your Collar” pop songstress Connie Francis, Dudek drifted to the guitar-heavy sounds of the Ventures and the unequaled songwriting and harmonies of the Everly Brothers and the Beatles. The British Invasion gifted Les with the Who, the Rolling Stones, and Cream.

By then, music was heavy on his mind. “I was about ten years old when I got the guitar bug,” Dudek said. He still has his first twenty-dollar 1965 Silvertone 604 acoustic guitar hanging on his wall. Disaster struck when he attempted to tune it for the first time. “I was turning the keys too high until I popped the string, and I thought it was the end of the world.” It turned out to be an easy fix. Taylor’s Drug Store in Auburndale stocked Black Diamond guitar strings right behind the counter.

His first electric guitar was a Silvertone 1446L hollow-body. It had black and white trim, reminiscent of the Gretsch Country Gentleman that Beatle George Harrison played. Dudek had spotted it in a Sears and Roebuck catalog and had to have it. It was a Christmas gift from his parents that year. “I have a picture of my mom and me on Christmas morning with that guitar – it’s a fond picture,” he said.

The future guitar great eventually discovered Carlton Music Center, a music mecca of 1960s Polk County. “I can remember hanging out at Carlton Music Center, running into Gram Parsons and Jim Stafford, Jon Corneal. We were all kind of a product of music back in those days.”

Later he’d go to other Florida music stores like Thoroughbred Music in Tampa and the Music Mart in Orlando, where he got a sunburst Mosrite Ventures electric guitar. He remembers showing it off to Carl Chambers. When Chambers leaned down to look at it, a Zippo lighter tumbled from his pocket. “It was like slow motion, how it drifted all the way down my guitar and put a big dent in it,” he said. Chambers felt terrible, but there was no harm done, Dudek was able to trade it out for a black one. Les would go on to do the same to Jim Carlton’s bass with his belt buckle. Jim still teases him about it.

The first band Dudek played with was a group of other local boys. “I don’t even think we put a name on it. It was just a bunch of kids in the neighborhood,” he said. Ricky Erickson was on lead vocals with Butch Buchanan on lead guitar, Rick Burnett on drums, and Gerald Enfinger on bass. He referred to this group as the ‘Marjorie Avenue Bunch.’ Erickson’s mother was the manager for the Dale Drive-In, where the boys would rehearse in the concession stand. A man walked up to the boys at the drive-in one day and said, ‘Hey! How’d you guys like to make some money doing that?’

He owned a trailer sales business next to what was Club 92. “The guy wanted us to set up in front of his trailer sales so we would attract people coming and going by the freeway there,” Dudek said. “He paid us each five bucks – that was our first gig.”

The young guitarist graduated to another band, the Steppin’ Stones, with David Shoemate on drums, Chuck Corneal (brother of drummer Jon Corneal and former mayor of Auburndale) on guitar, Butch Buchanan on lead guitar, and Dudek on bass.

He hopped out of the Steppin’ Stones into United Sounds, a ‘mirror image band’ of another Auburndale garage band turned legends – Ron and the Starfires. Dudek’s first mentor was an original member of United Sounds, Mitchell Smith. He would go watch Smith play with the band at the Auburndale teen center. After the show, Smith would show him things on the guitar and eventually taught him how to play “Johnny B. Goode” on his 1964 white SG Custom.

Carl Chambers was another local musician he looked up to. Dudek would skip school, pick up cheeseburgers from Taylor’s Drug Store, and show up at Chambers’ house. “I’d trade him burgers for some guitar licks,” he said.

The Polk County music scene was like a game of musical chairs with young musicians changing bands, forming new ones, and joining established ones – and Les was no different. “We were kids forming bands and playing teen centers and frat houses,” he said. “It was better than doing anything else criminal.” However, they would occasionally steal colored flood lights from motels to illuminate their band. They had a makeshift light bar where they’d screw in their freshly lifted flood lights.

After the Derry Down moved to Cypress Gardens Boulevard, the original building became the Pied Piper for a time. Les remembers playing the Pied Piper. The building had no air conditioning. “I remember it being a hot box,” he said.

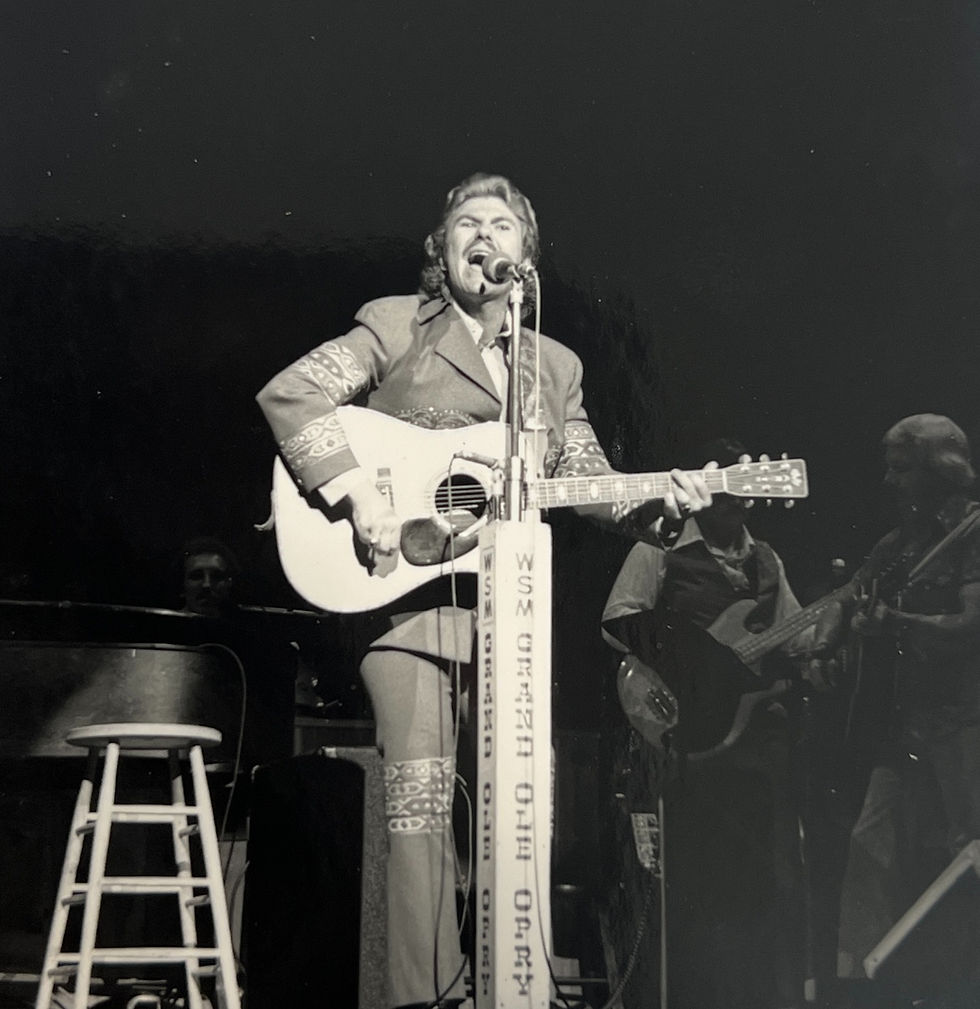

The last time he saw Gram Parsons was outside the Pied Piper. “I could tell from the way he was looking at the Derry Down he was kind of reminiscing what it was like when it was his place,” he said. Les, some six years Gram’s junior, struck up a conversation with the older musician.

Dudek moved on from the United Sounds to Blue Truth, followed by the third or fourth iteration of the band Power, playing high school dances, frat houses, and the Florida teen center circuit that was white-hot with rising stars. Back in the day, Florida “was like the east coast version of California, but not quite as hip yet,” he said.

Following Duane Allman’s death in a 1971 motorcycle crash, a founding member of the Allman Brothers Band, Dickey Betts, called on Dudek to play with him. Eventually, Betts and Dudek linked back up with the Allman Brothers Band, and Les played guitar for their hit song, “Ramblin’ Man.” He co-wrote and played some acoustic guitar on the song “Jessica” for the same 1973 Allman Brothers Band album, Brothers and Sisters. The success of “Ramblin’ Man,” which ascended to No. 2 on the Billboard charts, ignited Dudek’s career.

Dudek thinks back on that night in front of the Pied Piper occasionally. “I wonder if Gram got a chance to hear me play on “Ramblin’ Man” before he died.” The single was released in August 1973, and Gram died in September.

In 1973, Dudek met Boz Scaggs and went on tour with him for about five years, later playing on his 1976 album, Silk Degrees.

At the end of their The Joker tour, the Steve Miller Band tapped Dudek to work with them in Seattle. There, the band and Dudek cut songs that would end up on albums Fly Like an Eagle, Book of Dreams, and Living in the 20th Century.

The Steve Miller Band even covered the song “Sacrifice,” which Dudek had co-written with guitarist James Curley Cooke. “Sacrifice” made it onto the Book of Dreams album and Dudek’s first solo self-titled album, produced by Boz Scaggs and released on Columbia Records in 1976. This wouldn’t be the last of his songwriting successes either. Dudek co-wrote “Sister Honey” with Stevie Nicks for her 1985 Rock a Little album. The two also co-wrote the song “Freestyle” together, which Dudek would go on to name his 2003 solo record with E Flat Productions.

While living in California circa-early-70s, another offer would come Dudek’s way. Manager and musician Herbie Herbert approached the guitarist about a new band he was forming. Herbert told Dudek, ‘I want to get the two guitar heroes from the San Francisco Bay area to be in the same band.’ Dudek thanked him for the compliment and asked who the other guitar player was. It was none other than Neal Schon, guitarist, for Santana, along with bassist Ross Valory.

Dudek was set to meet the other would-be members at a rehearsal hall called Studio Instrument Rental in San Francisco. He received a call from Columbia Records’ A&R department requesting a meeting at one of their studios which happened to be right across the street from the rehearsal hall. “I was going to be on that side of town anyway that day rehearsing with this new band called Journey,” he said.

Two hours into the Journey jam sesh, Dudek stepped across the street to take the meeting with Columbia Records. He was offered a solo deal on the spot. Weighing his options, Dudek decided to go solo. He laughed, recounting the story, “It turns out I was one of the founding members of Journey for about two hours.”

Following his debut album, Dudek worked on Say No More with audio engineer and record producer Bruce Botnick, famous for his work with the Doors, the Beach Boys, and Eddie Money. This era of Dudek’s career garnered him offers from various artists and bands, including the band Chicago after the 1978 death of member Terry Kath. The manager for Little Feat offered Dudek the job when Lowell George passed away in 1979. Around the same time, Bob Dylan and Eddie Money also sought out Dudek, but he was already immersed in his own projects.

Dudek recorded five albums with Columbia – four solo and one with a band. In the late 70s, he linked up with Mike Finnigan and Jim Krueger. The two had been working with Dave Mason. Krueger wrote the song “We Just Disagree” for Mason. Their band would be called the Dudek, Finnigan, and Krueger Band (DFK).

The promotion for this band was a bit ‘ass backward,’ as Dudek would say. Instead of cutting a record together and touring to promote it, the three were each promoting their solo albums. “It was really a confusing thing for the audience,” he said. DFK did go on tour with Kansas for about four months and worked with artists like Kenny Loggins and Dave Mason. “Then we got the bright idea – why don’t we do a DFK album,” Dudek said. The Dudek, Finnigan, and Krueger Band released their first and only self-titled album with Columbia Records in 1980.

While on hiatus with DFK, after he’d cut his third record, Gypsy Ride, Dudek got a call to go to an audition for Cher. The Goddess of Pop was looking to start a rock band called Black Rose. DFK’s Mike Finnigan turned up at the auditions along with Steven Stills of supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young fame. “We turned it into a big jam session,” Dudek remembered.

After the auditions, Cher invited them all for dinner at Nick’s Fishmarket in Beverly Hills. She asked Dudek if he was serious about helping her start a band. Sure, he told her. “I wasn’t doing anything else.” Les Dudek became the Black Rose band leader and recommended esteemed composer James Newton Howard, whom he had worked with on the DFK album, to produce the Black Rose record.

In the interim, Cher and Les (or LD as she sometimes called him) began dating. “We had already been dating, and she said, ‘LD, why don’t you just move in?’” Dudek said. He lived with her for the better part of three years.

Dudek named the founder and president of Casablanca Records Neil Bogart as the short-lived band’s biggest champion. Black Rose would release one self-titled album in 1980, appear on The Merv Griffin Show, and host The Midnight Special alongside the Rolling Stones and the Everly Brothers the same year. Cher also appeared on Tom Snyder’s Celebrity Spotlight to promote the record. Black Rose wilted following Bogart’s death and Dudek and Cher’s breakup in 1982.

According to Dudek, he encouraged Cher to pursue acting post-Black Rose. A few years after parting company, she called him up and said, ‘Hey Les, I’m doing a new movie, and they’re looking for a guy that’s got long hair, sings, plays guitar, and rides a motorcycle. Do you know anybody like that?’ That’s how Les Dudek got his first film role as Bone in director Peter Bogdanovich’s 1985 movie, Mask. Dudek followed that up with a television movie, Streets of Justice, released the same year.

The highly sought-after southern rock guitar god continued to tour around Europe and the United States in the 1990s. He released three albums through his own record label, E Flat Productions, including Deeper Shades of Blues in 2001, Freestyle in 2003, and Delta Breeze in 2013. He still tours around Florida, including appearances at Gram Parsons Derry Down.

NUDIE SUITS IN NASHVILLE

“All I wanted to do was play drums,” said The Legendary Jon Corneal, pioneer of country rock drumming. He started as a little boy from Auburndale who hated playing the baritone his parents rented him for ten dollars a year.

When he was four, Corneal’s ‘momma’ took him to watch the Winter Haven High School Marching Band. He told her then that he wanted to play the ‘dwums.’ (This was before he’d taken three years of speech therapy.) “I ruined a lot of furniture with knives or forks beating on it,” he said. Corneal told his parents that if they’d permit him to play drums, they could save their ten dollars a year because he’d buy his own. The Corneals relented, perhaps more to save their furniture and silverware than the money. Jon’s father owned a lumberyard, and the family lived in a spacious brick Tudor-style home on Lake Juliana, built in 1925. “It’s as nice as any Snively house,” he said. Corneal had his own garage apartment when he was twelve.

When the decision was made to drop his baritone and pick up drum sticks, Corneal had to return to the beginner band. His band director, Mr. Miller, would take Jon from Auburndale Junior High to Auburndale Primary School in his 1956 Chevrolet. He started all over with drums, but within a month or two, Corneal had caught up and returned to the intermediate band at the junior high. Though he learned how to read music, Corneal didn’t put too much stock in it. He mentioned a line by The Country Gentleman, Chet Atkins, who once said when asked if he read music, “I do, but not enough to hurt my playing.”

Jon set up a drum kit to practice in his apartment above the garage of the Corneal home. When he wasn’t working for his father at the lumberyard, a young Jon Corneal played that drum kit with zeal, practicing until 10 pm on school nights, prompting his mother to beat on the garage ceiling with a shovel and yell, ‘You got school tomorrow, you need to quit!’

Later, when Corneal played with the Legends, they’d occasionally practice in that garage apartment. “We’d either rehearse at my place or in Gram’s room,” he said.

Before joining the Legends with Gram and the gang, Corneal was in a band called the Dynamics alongside Carl and Gerald Chambers. The Dynamics, like most garage bands of the era, would add and change members, including Bobby Braddock, Aaron Hancock, Buddie Canova, Randy Green, and Billy Joe Chambers. The band would travel to play at different Central Florida teen centers. “My momma would let me borrow her Oldsmobile. […] You could put all the drums and all our gear in the Olds because they were big cars, so that was real handy.” Corneal remembered taking his mother’s Olds to a show in Kissimmee where each boy earned $10. “We were happy to get it, boy. We were making that money,” he chuckled. “Those were the days.”

His days in the Dynamics were numbered when Gram Parsons scouted him at the Auburndale municipality building. “That’s where we were rehearsing that afternoon,” Corneal said. “He liked Gerald [“Jesse” Chambers] and my playing, and he needed to replace a bass player and a drummer, so he got our numbers.”

Gram called up Chambers and Corneal, and they met up and “started running some tunes together.” In 1962, Chambers and Corneal officially became Legends with Jim Stafford on lead guitar and Gram Parsons on keyboards, guitar, and vocals.

One appeal Gram had for Corneal was his ability to secure paid bookings for the band like that horse show banquet, where the Legends played in the ballroom of the Haven Hotel. That year between the banquet, Christmas parties, and New Year’s Eve gigs, the boys made more than a little scratch.

“Growing up in Auburndale, the coaches hated musicians. If you were a musician, you were so less than – way, way down low on the totem,” he said. When they returned to school following the holidays, the coach started giving him grief. Corneal laughed as he told the story. “I said, ‘Hey coach! How much money did you make last week?’ He wouldn’t tell me. I said, ‘Well, if you didn’t make $300, I made more than you did.’ And he never called me a sissy again.”

Corneal appeared on WFLA channel 8’s, Hi-Time with the Dynamics and later with the Legends, winning Hi-Time’s Band of the Year.

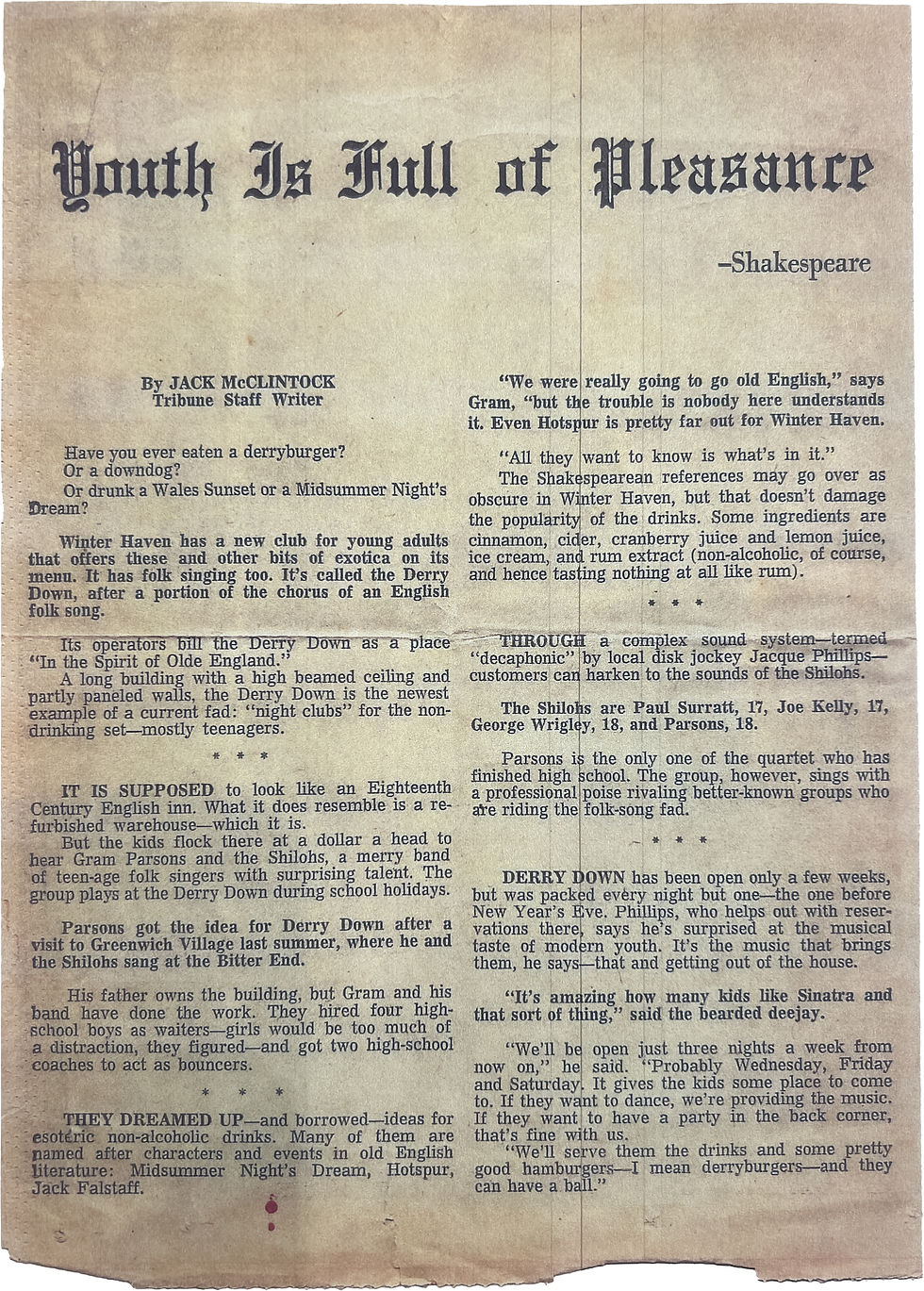

In early July 1964, fresh out of high school, a 17-year-old Jon Corneal and Eloise guitarist Jim Stafford put Polk County in the rear view, pulling a 13-foot Scotty camper. A few days later, they pulled into an RV park, spot E15, Corneal still remembers, in Nashville, Tennessee. The two would eventually split company to pursue their individual entertainment aspirations. One of Corneal’s Nashville neighbors, bass player for Flatt and Scruggs and The Foggy Mountain Boys, Jake Tullock, lent him the money to join a musician’s union that August.

Most of the country acts of the time didn’t care for Corneal’s brand of drumming. He referred to himself as a ‘fancy solo drummer’ in addition to the group work he played. “When I played with the Legends, I’d do a ten-minute drum solo, and they’d all leave the bandstand,” he said. The newly-graduated teenager was often surrounded by artists twice his age in the Music City. “They’d turn to me and say, ‘Keep it country boy, keep it country! Stick and a brush!’ You never told a rock and roll drummer not to play with two sticks,” he said. “I decided if that’s all I could do, I’d learn how to keep time that was better than a metronome. I learned where the pocket is, for sure.”

In 1965, Corneal got the part of a drummer in the Nashville musical film, Music City U.S.A. (1966). According to Corneal, he got fellow Auburndale native and Dynamics bandmate Bobby Braddock a part playing piano for the movie. Corneal said, “He told the makeup lady to just do the back of his ears because they had him playing an upright piano, and he wasn’t facing the camera. I thought that was funny.”

It was through Music City U.S.A. that Corneal met country music duo the Wilburn Brothers and legendary singer-songwriter and future Country Music Hall of Fame inductee Loretta Lynn, who were featured stars in the film. The former would go on to offer Corneal a job, and he spent the whole of 1966 as the drummer for the Wilburn Brothers. The band was in high demand, packing out the most prominent music halls, theaters, and auditoriums throughout Texas and the southeast. “Back then, they’d still turn 2,000 [people] away,” Corneal said. The Wilburn Brothers played with Loretta Lynn plenty around this time as she was signed with their agency, the Wil-Helm Agency. “Back then, she had her own band, so we backed her up on a lot of shows.” Describing her with a drawn-out emphasis as ‘cooooun-try,’ he added, “She was a darlin’ – she was the sweetest thing.” That year, Corneal played on Lynn’s Christmas album, Country Christmas.

So, there he was, on the road playing with some of the best country musicians of the time. “But I was frustrated,” he said. “When I’d come home, I’d borrow a guitar and start writing songs, working on my singing more and more.”

In 1966, Corneal saved up the $100 per week salary he was making with the Wilburn Brothers to book other musicians and record five of the songs he had written at Bradley’s Barn in Nashville. That was his seminal country rock session.

His country rock roots and connection to former bandmate Gram Parsons would soon bring him to the glitz and grit of Los Angeles. Every so often, Corneal, a true-blue Florida boy, would head south to the Sunshine State to drive the old dirt roads. “I used to come home to smell the orange blossoms,” he said. During one 1967 trip home, Gram was also in town from California, where he’d been pursuing music post-Harvard. He asked Corneal to come over so he could play him some new music he’d discovered.

On a Robert’s reel-to-reel recorder, Gram played Jon a compilation tape he’d made with the country croonings of Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, and Loretta Lynn.

It was surprising to Jon that Gram had ‘discovered’ this sound. “I’d been playing it for a couple of years already and making records and playing on people’s recordings […] making a living playing music,” Corneal said. The spring prior, Corneal said Gram had given him a hard time about the country music he was playing. “He had this attitude about me playing country. People in rock and roll didn’t like country, thought it was less than.” Gram would reproachfully ask Corneal, ‘What are you doing playing that country?’

“That’s where the work was, and that’s why I took it,” Corneal confessed. “I went up there [to Nashville] hoping I could get with the Everly Brothers or Roy Orbison.”

On the same trip home, Gram asked Jon to join the International Submarine Band in California with the agreement that Jon could sing and play some of his songs. “They flew me out first class, so I got steak and lobster and champagne twice – out of Tampa and out of New Orleans. I was feeling no pain when I got there,” Corneal said, smiling.

Los Angeles would prove a big shock for this southern Bibleraised Boy Scout. One morning Gram invited Jon over to actor Peter Fonda’s house for a swim. Sure, he’d go, he said. “As it turned out, I was the only one that had a bathing suit. […] I’d never seen anything like it.” Asked if he’d slipped off his skivvies to join in on the skinning dipping, Jon said in his unhurried southern drawl, “No, ma’am, I didn’t take it off.”

As it would turn out, Gram’s promise to give Corneal some time out front remained unfulfilled. A fight over this prompted Corneal to part ways with the International Submarine Band – that ship had sunk, and Corneal was stranded. LA proved a hard place to adapt for Corneal, who described the city as ‘a different world.’ “There was a few years of struggle there.”

Corneal would go on to record percussion for the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo album, with his name listed alongside drummer Kevin Kelley in the album credits.

Less than two years after playing with the International Submarine Band, Corneal would answer Gram’s call again, this time to play with his band following the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers. After arriving in California, Corneal would hop from Gram’s couch to ‘Burrito Manor.’ The first Flying Burrito Brothers album, The Gilded Palace of Sin, features Corneal’s percussion on five songs. He left the band shortly after recording the album and returned to Nashville. He still has the Nudie suit to show for his time with the Flying Burrito Brothers. “We went to Nudie’s and got measured. I told him I wanted a red suit with an Edwardian collar, with palm trees and all kinds of rhinestones, gold alligators, and on the back was a riverboat,” he said.

These rodeo and rhinestone Nudie suits were designed by Nudie Cohn, founder of Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors in North Hollywood. Elvis, Gram, Dolly, Porter, Buck, Cher, Sly – Nudie suits have been the flashy regalia of country-western and pop culture royalty, then and since.

Corneal must have felt like the picture of snaz, rhinestones reflecting in infinite directions. “That’s the magic of those things.

When you walk out on stage wearing those things, you’re like more than human. There’s something extra going on there. It’s so showbiz-y, it ain’t even funny.”

Earlier this year, in February, Corneal’s friend and Derry Down Project champion Gene Owen accompanied him to Nashville to deliver the garments to the Country Music Hall of Fame to be included in a future exhibit at the museum. The official loan document lists: “Nudie costume jacket with submarine imagery plus nudie jacket with riverboat imagery and accompanying pants worn by Jon Corneal.” The Nudie jacket with submarine imagery was Gram’s from the International Submarine Band, worn during a cameo in The Trip (1967) starring Peter Fonda. Gram gave it to Corneal in 1972 when the percussionist drove to LA to fill in during rehearsals for Gram’s band, the Fallen Angels.

“We don’t often in our lives get treated special,” Corneal said of his time delivering his Nudie suit and sitting for an interview at the Country Music Hall of Fame. “But they treated us special.” In addition to the loan of garments, Corneal is contingent on making appearances at the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Following his work with the Flying Burrito Brothers, Corneal played on Warren Zevon’s Wanted Dead or Alive album and then with ex-Byrd Gene Clark in the band Dillard & Clark on their second LP, Through the Morning, Through the Night. He went on to tour and record with the Glaser Brothers and eventually broke out on his own in 1973, releasing Jon Corneal & the Orange Blossom Special in 1974. He has performed around Florida in his group Limousine Cowboys and for some 30 years with his wife in their act, the Jon & Debbie Corneal Show.

“I dreamed about being a star and having my own bus and playing all these places on my own instead of working behind the star,” Corneal said. “I’ve had all kinds of people standing in front of me, doing their thing, and I’m just back in the back playing the drums, wishing I could be upfront singing.”

Now, every Friday at ‘high noon’ at Hillcrest Coffee in Lakeland, The Legendary Jon Corneal and His Compadres play a live two-hour set in which Jon sits front and center. They live stream with people tuning in from all over the world to see a world-class band, headed up by Corneal on drums and rhythm guitar, improvise a set of classics and original music. “I always tell people, his recordings, yeah, they’re pretty damn good, but you’ve got to come see him,” Gene Owen said.

Jon’s Compadres are a floating cast with a nucleus of regular players. “We have patrons that have been faithfully contributing and supportive. It kind of amazes me,” Corneal said. He may have been a ‘road dog’ as a young man, but Corneal is glad to have a home base in Hillcrest Coffee. “Having a place to play once a week and not having to travel is pretty neat.”

The country rock drummer recorded his most recent album, High Country, in 2019. The record is a mix of American classics and Corneal’s original music. The first song on that album, “Used To Do,” was a rendition of one of Corneal’s 1965 formative country rock recordings. On the album’s inside cover, Jon thanks many people, including pal Gene Owen, Compadre Buster Cousins, wife Debbie, “Brian Goding, and all my friends and family at Hillcrest Coffee,” and “my Lord and Savior who has given me the way.” In addition to his Friday concerts with the Compadres, Corneal hosts a weekly Bible study at the Lakeland coffee shop.

A former Legend, now legendary, Jon Corneal continues to make music. At 75, his drumming is still meticulously in-time – ‘better than a metronome.’ When he catches a show at the Derry Down, he’ll graciously regale Gram fans with stories about the cosmic icon, also inviting them to see him play sometime. Between his appearances at the Derry Down, Hillcrest Coffee, the Country Music Hall of Fame, and the ubiquity of social media, the pioneer of country rock drumming said, “Finally, people are starting to figure out my contribution.”

SAVING THE DERRY DOWN

In 1964 Gram Parsons would open a teen club in a little building on Winter Haven’s Fifth Street. By 2012, the defunct Derry Down had become a warehouse lost to time. The relic of Polk County’s musical paramount was in disrepair and being used for storage. Not everyone had forgotten it, though. The convergence of an author, a persistent Gram fan, a nonprofit, a private developer, and the Winter Haven community would save this cultural landmark in the eleventh hour.

Ten years ago, Bob Kealing released his book, Calling Me Home: Gram Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock. The author, an Edward R. Murrow and four-time Emmy award-winning broadcast journalist, is no stranger to writing about Florida figures and history – it’s kind of his thing. “My raison d’être is preDisney history. When I got here 30 years ago, I really started to bristle at this notion that Central Florida has no history or culture that predates Walt Disney,” he said.

In the mid-nineties working as a freelance writer and reporter with the Orlando NBC television affiliate, Kealing began investigating novelist Jack Kerouac. He learned about a thendilapidated Orlando cottage Kerouac shared with his mother in 1957 and 1958. In 1997, Kealing penned a four-thousand-word article about the cottage for The Orlando Sentinel, sparking what would become the Kerouac Project. An all but forgotten abode twenty-something years ago, the Kerouac house is now a fully restored home on the National Register of Historic Places. An ongoing writers-in-residence program is hosted there. In 2004, Kealing published the book Kerouac in Florida: Where the Road Ends.

Throughout the four-and-half-year process of researching and writing Calling Me Home, Kealing traveled from Waycross to Winter Haven, visiting sites relevant to Gram’s story. He interviewed Gram’s best friend, Jim Carlton, for an early background on the country rock pioneer. “I’ll never forget Jim standing in Gram’s old room and just going, ‘Oh my God, the memories are just coming flooding back,’” Kealing said. It was the first time in 40 years Carlton had been back there.

Kealing had heard about this Derry Down place – Gram’s old teen club. Carlton offered to show him where it was, just a minute or so walk from his family store, now owned by his cousin Glen, Carlton Music Center.

The author looked through a side window of the derelict Derry Down. The building was in shambles and filled with junk. Looking inside “triggered a lot of memories” for Gram’s childhood friend. Carlton still had the reel-to-reel recordings he’d taken when the Derry Down opened in 1964. He shared those with Kealing too.

An entire chapter is dedicated to Gram’s senior year and the opening of the Derry Down in Kealing’s book. Only a few paragraphs into that chapter, he wrote:

It’s surprising there isn’t already a more permanent memorial here. For fans of cultural tourism, the corridor between Winter Haven, Auburndale, and Lakeland would be an ideal place to create some sort of tribute to all the musicians who called this area home in the 1960s.

Kealing included a photo of the former Derry Down. The shabby warehouse was in rough shape and demolition seemed inevitable.

The universe must have read that passage loud and clear. Certainly, self-described mega-Gram fan and local music historian Gene Owen did.

“I think Gene Owen was an important catalyst in bringing all of it together,” Kealing said.

In August 1968, Owen bought the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo record. He put it on the turntable at his Lakeland home, and by the end of the fifth song, “You’re Still on My Mind,” Owen was a Parsons devotee. “It was like something from outer space to me,” Owen said – an apt description of Parsons’s Cosmic American Music. “I just got chills even thinking about that day.” He had no idea that Parsons grew up not 15 miles from there.

Owen would also get a chance to look in the Derry Down by way of former Legends drummer, Jon Corneal. The two met in 1977 when Owen and a friend were driving along Highway 92 in Lakeland and spotted a sign promoting a show for Jon Corneal and the Limousine Cowboys. Owen had seen Corneal’s name in the credits for Sweetheart of the Rodeo and The Gilded Palace of Sin and had to stop to see him play. Jon and the band were outside taking a break when they pulled up. The two got to talking and have been friends ever since, sharing an interest in music and cars.

After that celestial experience listening to Gram, Owen consumed as much media and music related to the musician as existed. “I had read all the Gram books probably twice by the time Bob’s book came out,” he said.

One day, after reading Bob Kealing’s book, Owen picked up Jon Corneal to show him a 1970 Mercedes sedan. Corneal got in the car, and Owen told him about the book and the Derry Down. Corneal knew right where it was – he’d already been there fortysomething years earlier.

When they rolled up to the Fifth Street warehouse, the Cosmic American Music gods smiled down on them. A Six/Ten employee happened to be at the building. He shuffled through his ring of keys and let Owen and Corneal have a look inside. “I had out-ofbody travel, I swear,” Owen said.

Around the same time, Six/Ten President and Secretary Kerry Wilson was on a bus, reading the book. Wilson later relayed to Kealing that he saw the warehouse and thought, ‘Wait a minute, we own that building!’

When Main Street Winter Haven Director, now President and CEO, Anita Strang caught wind of the Derry Down site, she rushed to The Shop to get a copy of the book.

Motivated by the historical significance and potential of the Derry Down, Gene Owen reached out to Kealing. He asked the author to do a book signing in Winter Haven. Owen told Kealing, “Listen, there’s some pent-up demand for Gram in Winter Haven. You’ve got to know this.” The Calling Me Home author agreed, and Owen coordinated a book signing to be held on February 16, 2013, at the Winter Haven Public Library.

Owen was right about the ‘pent-up demand for Gram’ as some 200 people packed into the library to hear Kealing, Jon Corneal, and Jim Carlton speak. A community that knew Gram, or grew up on his music and mythos, hung on every word. Main Street Winter Haven Director Anita Strang was there too.

“The fact that there were so many people at that book signing was an indication that everybody thought, ‘Hey, we’ve got something here,’” Kealing said.

After the signing, about half the crowd walked from the library to the Derry Down. “I was a little taken by how many people had come to this,” Strang said. A man walked up and asked if the building had a plug because he had something to play – it was Gram’s friend, Jim Carlton. In the dilapidated Fifth Street warehouse – attendees listened to a reel-to-reel recording of the Shilos performing during the 1964 opening day of the Derry Down. “You could hear this super sweet southern voice talking and playing,” Strang remembered.

Standing by the door as people made their way through the building two at a time, she heard folks sharing their memories – a first kiss here or a dance over there. “It was really apparent that whatever this was, meant so much to people here,” she said. “Time goes by, maybe about a month, and then the visits start from Gene Owen.”

“I’m a relentless kind of a character,” Owen said. He’d stuck his neck out already by inviting Kealing to speak. Members of the Chamber of Commerce, commissioners, and city officials had attended the book signing. He remembered thinking, “If this doesn’t happen, I’m going to have to move.”

Owen wanted Strang to do something to preserve the Derry Down within her capacity as Main Street Winter Haven director, but her hands were tied. The building was privately owned. She encouraged Bob Kealing, who was also advocating to save the Derry Down, to set up a meeting with Six/Ten. Over lunch, he laid out a case for the building’s historical value and convinced them not to demolish it.

Inspired by the idea of the Derry Down as an avenue for cultural tourism, Strang began digging further into Gram Parsons’s life and his ties to Winter Haven. She sought the guidance of state and national coordinators for Main Street to determine if this project was even within her organization’s scope. “I wanted to make sure, from the Main Street perspective, that this could benefit downtown in multiple ways, more than just saving this building and having a place for [Gram’s] legacy,” Strang said. “Could this become something good for our downtown?”

Emphatically, yes was the answer from Main Street. It was worth the time and energy to save, but the building had to be donated. After negotiations between Main Street Winter Haven and Six/Ten, the acquisition proceeded. The building would be donated but deed-restricted for the use of music and music education, along with the ability to rent it out to offset costs.

“We knew the current board understood all of this,” Strang said. “We were looking to protect the building long-term, to make sure that 10 or 15 years from now, that board of directors knew they had to use this building for the right reasons.”

Around the time of the building’s donation, Strang remembers meeting with Kealing, who accompanied her to his first project, the Jack Kerouac House. The trip was motivating for Strang. The revived cottage was emblematic of the transformation that was about to take place on Fifth Street – what a vision of that magnitude realized could look like.

The Derry Down Project commenced on June 20, 2014. It would take two-and-a-half years to restore Gram Parsons’s teen club to its 1964 glory.

With the building donated and everyone united for the cause, it was time to start fundraising. It needed a lot of work. “Three of the trusses had fallen, and it was taking on water – the building was coming apart,” Strang said.

The first dollars raised for the restoration weren’t even within the city. A Parsons fan from Atlanta caught wind of the project online and set up a fundraising show with multiple concerts to save the Derry Down. Strang attended the event.

People from around the world would send amounts large and small. Strang remembered receiving a $10 donation from Thailand – a testament to Gram’s cosmic reach and impact.

Main Street hosted a series of open houses, promotional events, fundraisers, and workdays to restore the historic site. The first big event was held on December 20, 2014, exactly 50 years from when a young Gram Parsons took the stage with the Shilos and sang “Big Country” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out” on the Derry Down’s opening day.

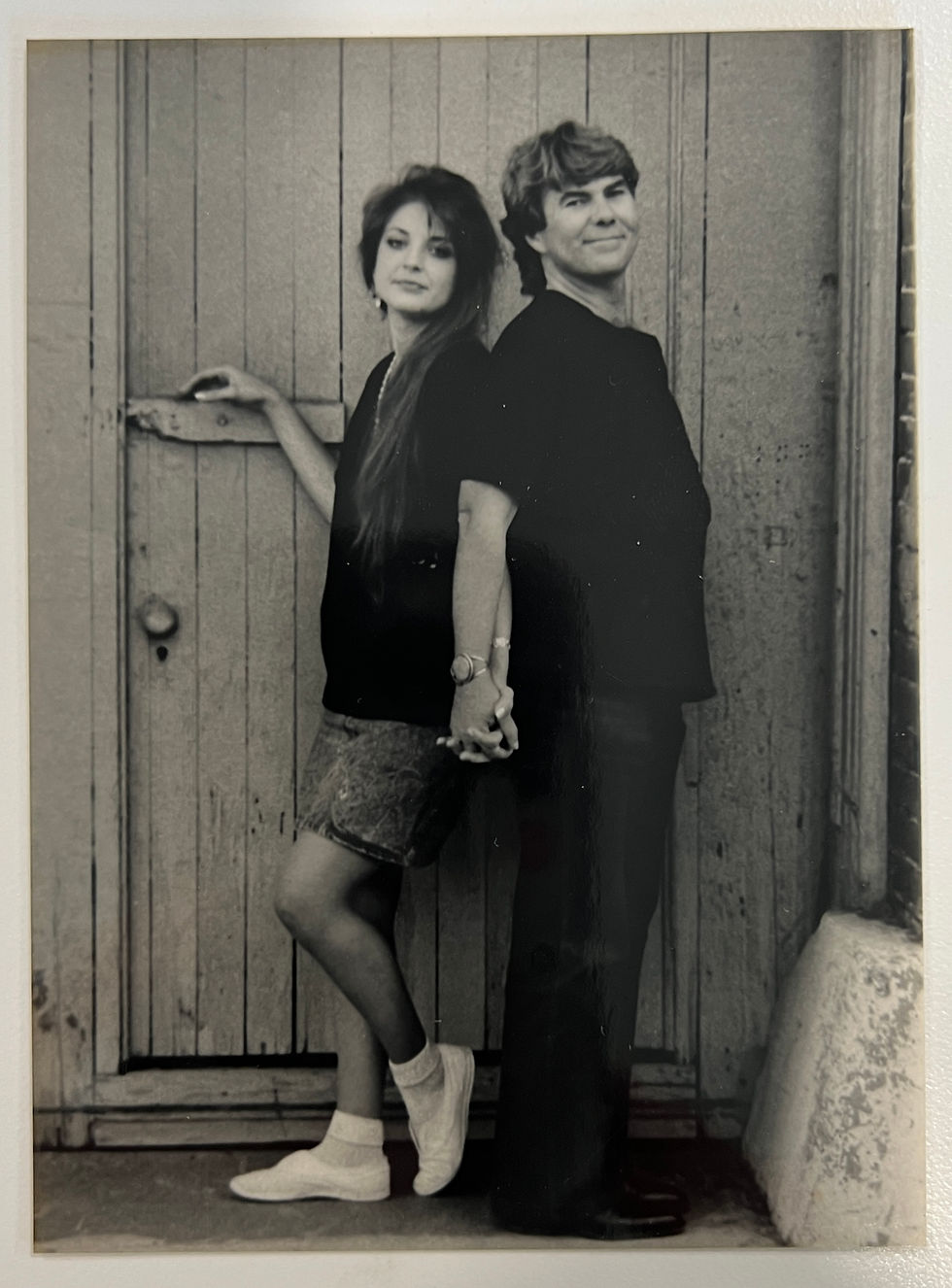

A stage was erected in the middle of Fifth Street where former Legends members Jon Corneal, Jim Carlton, and Jim Stafford performed as a group at the Derry Down for the first time ever. “King of Broken Hearts” singer-songwriter Jim Lauderdale headlined the event.

In 1985, Lauderdale moved to Los Angeles on a sort of Parsons pilgrimage. “I wanted to play at some of the same places, be in the atmosphere that he had been in, walk the streets he had walked, drive the roads he’d driven, and try to soak up more about him,” he said.

Already aware of the Derry Down through reading various Gram biographies, when Lauderdale learned it was being restored, he jumped at the chance to be involved – another stop on that pilgrimage. The building wasn’t ready for show occupancy on that day in 2014, but Lauderdale got to peek inside. “For me, who’s such a huge fan of Gram’s, that just was so important to me to get to be in that space where he had performed,” he said. While Parsons’s contributions to music with the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and as a solo artist are important, Lauderdale said, “It’s equally important to go back to the very early roots.”

Winter Haven guitar genius Les Dudek also pitched in his musical talent, playing the Derry Down to raise money at various events. “When they got all excited about it, so did we. We were all, ‘Let’s save the Derry Down!’” he said.

At the open houses and fundraisers, Strang dedicated a place for guests to write down their memories from the teen club. It was essential to the Main Street Winter Haven director to preserve the Derry Down – bones and soul – to collect these stories for posterity along with the building’s physical restoration. Strang has held onto these handwritten echoes from the sixties in a box for safe-keeping.

Winter Haven photographer Mike Potthast produced a video featuring Bob Kealing, a musician who grew up with Gram, Jerry Mincey, and Anita Strang, summarizing the project for a Kickstarter campaign. The campaign, unfortunately, did not meet its goal, which meant the Derry Down Project received zero of the funds pledged. But, Main Street Winter Haven, Bob Kealing, Gene Owen, Six/Ten, and the community of Winter Haven pressed on.

“When I say that building belongs to the community – it belongs to the community,” Strang said. She was stunned by the local business and individuals who offered up money, time, and resources.

Gene Owen, a founding father of the Derry Down Project, said, “I’m heart warmed by the whole thing.” He couldn’t have predicted the community commitment to seeing the project come to fruition. While donations came in from around the world, the brunt of the time, love, and labor came from Gram’s hometown. Companies and organizations like New Electric, Whitehead Construction, Burns Flooring and Kitchen Design, SJMS Plumbing, Six/Ten, and the City of Winter Haven were wholly involved “head and heart” in the Derry Down Project.

During the restoration, Strang pushed to preserve aspects of the original structure. Exterior lights were specially made to replicate the originals. The red interior paint color hadn’t been touched since the Derry Down opened. They were able to take a chip off the wall and color-match it. And Strang has that color on good authority – she talked to the man who painted it over a few beers, some weed, and gospel music with Parsons himself in 1964.

The Derry Down was located next to the Gilmore Pontiac dealership in 1964. It had a life as a car shop after it was Gram’s teen club. According to the Main Street director, the central beam was used to hoist motors from cars, adding weight to the roof, which would need to be repaired, or, as was argued to Strang, replaced. “The wood roof – that is the character,” she said in opposition to replacing the original roof. The community stepped in yet again when Winter Haven company Mechanical Dynamics found a solution to save it.

When all was said and done, over $160,000 was raised by the Main Street Winter Haven Board of Directors and the Derry Down Committee. In-kind labor and materials were estimated at $185,000.

The Derry Down received a historical marker from the Florida Department of Historic Resources on November 5, 2015. Gram Parsons Derry Down opened with an official ribbon cutting on September 2, 2016.

In 2017, Main Street Winter Haven was awarded the Outstanding Florida Main Street Rehabilitation Project from the Secretary of State for the Derry Down Project.

Cherished Polk County musicians like Jim Stafford, Jim Carlton, Jon Corneal, Gerald “Jesse” Chambers, and Les Dudek have played at the Derry Down since its 2016 reopening, some multiple times. Other figures from Gram’s career have also made it a point to perform at the venue, like International Submarine Band bass player Ian Dunlop and Parsons’s songwriting partner in the Flying Burrito Brothers and Byrds bassist, Chris Hillman. Gene Owen described Hillman’s April 30, 2017, Derry Down appearance as a “tremendous, redemptive, rejoiceful day.”

Multi-Grammy Award-winning singer-songwriter Rodney Crowell has even taken the Derry Down stage. He worked closely with Emmylou Harris after Gram died. “Rodney being in the building was just ethereal,” Owen said.